Part 1 is here. This post was originally published on Giap.

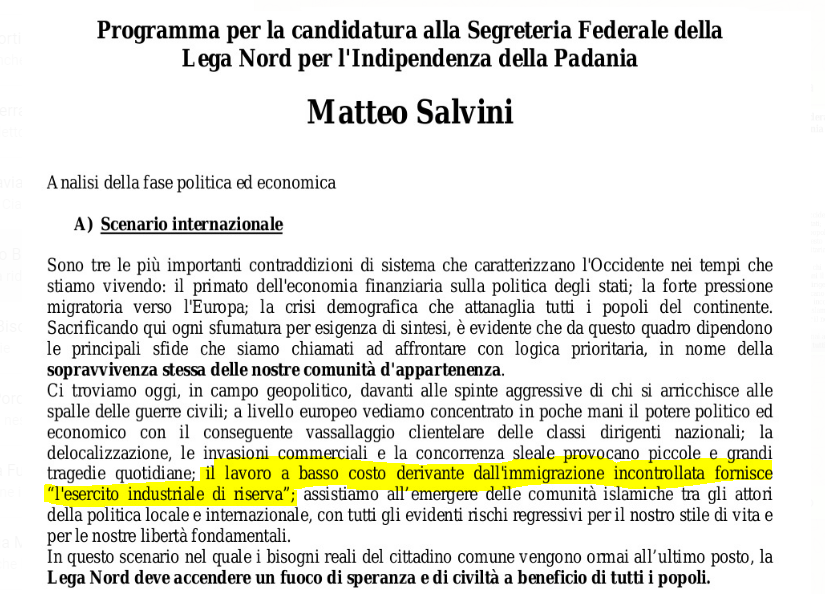

“We all have a friend, a lover, a relative, a neighbour or a colleague who was unequivocally left-wing until a few years ago, but who has recently begun reading weird blogs, following perplexing Facebook pages, quoting certified bullshitters as if they were independent maîtres à penser, and echoing Matteo Salvini’s ideas—with a communist twist…”

A spectre flies us to places of class struggle, where you can see that certain types of “Marxist” talk against immigration not only aren’t Marxist at all but are also a scam against workers. Against all workers, immigrant as well as local workers.

by Mauro Vanetti

editing: Camillo A. Formigatti, Roberto Amabile

translation: Antonio Scendrate, Ayan Meer, Camillo A. Formigatti, Claudio Mirabella, Daniele Contardo, Davide Tessitore, Filippo Ortona, Giovanni Vimercati, Marcello Bernardara, Mauro Vanetti, Niccolò Barca, Roberto Amabile, Simone Rossi, Stefania D’Urso, Tomaso Perani, Valerio De Sanctis

Contents of the second episode:

- Third night

- No-Border Lenin

- The last night

- In the good ol’ days… you would have grossed out the Left just the same

- Postscript

6. Third night

Now he was gaining confidence. He was already down the street, leaning against a wall.

“Well done! Climb up!” screamed Marx’s ghost while throwing an incredibly long rope ladder at him from a very distant point up in the sky. The rope unrolled until it almost touched the ground. It swung peacefully in front of Diego’s nose.

“Move your arse!” shouted the thunderous voice from above. The young man was terrified to his very core but, one trembling step at a time, he climbed between the buildings, over the fog, towards the stars, up to the lowest clouds. Every moment he feared he might fall but he dared not disobey the famous philosopher, dead in 1883.

Finally, he climbed over the parapet of the wicker basket and saw Marx manoeuvre the ropes and the flames of the hot-air balloon.

“OK. No jet this time, we have to travel during the daytime and we will watch from afar. You could use that spyglass, it has a good zoom.”

Diego could not help himself: “Dear lemur, master, but why call it ‘jet’ when you could use a beautiful Italian word, ‘aviogetto’? Also, why ‘zoom’? ‘Ingrandimento’! And the same goes with ‘OK’…” Marx tensed up at once. He screwed up his eyes under bushy eyebrows and gnashed his teeth. He relinquished control of the airship.

“First of all: lemur, my arse.”

“But it means nocturnal spirit! From Latin.”

“I know! But nowadays you just find little monkeys on Google. Language evolves, you dullard.”

“I see.”

“And where does this baloney against using foreign words come from? What is this linguistic defence of the fatherland? Workers have no fatherland. And if you ever read half a page of my works, I put in a foreign word every two lines. If it’s English, I put in some French. If it’s German, I put in some English. If it’s French, I put in some German. How could you be a man of culture in the nineteenth century without being a bit of a cosmopolitan? And you keep spouting this bullshit even though you’re from the twenty-first! Bugger off!”

“I apologise.”

“You are forgiven. Now, I’ll keep driving this contraption and you stop busting my balls. OK?”

“Understood.”

“No! You must say ‘OK’.”

“But… please… I can’t…”

“Say it!”

“O… K.”

“Parfait.”

The balloon was made of a dark red fabric on which was written, in an elegant nineteenth-century golden font, the brand name ERMEN & ENGELS. “Don’t even try to ask me,” muttered the lemur.

Before dawn, the light from the sleepy metropolis made it easy to find one’s bearings. “That’s Rome!” said Diego with excitement. The spectre yawned and held their course, letting the capital city slide away to their left.

A couple of hours later, after seeing other smaller towns, an important city, laid out in a gridiron pattern, started to appear in the middle of a patchwork of rectangles of various green shades, fruit and vegetable crops.

“I recognise it! It’s Littoria!”

Marx glared at him.

“Latina, I mean. Latina …,” Diego corrected himself.

“Do you know what a Sikh is?” asked the old man.

“An exotic creed.”

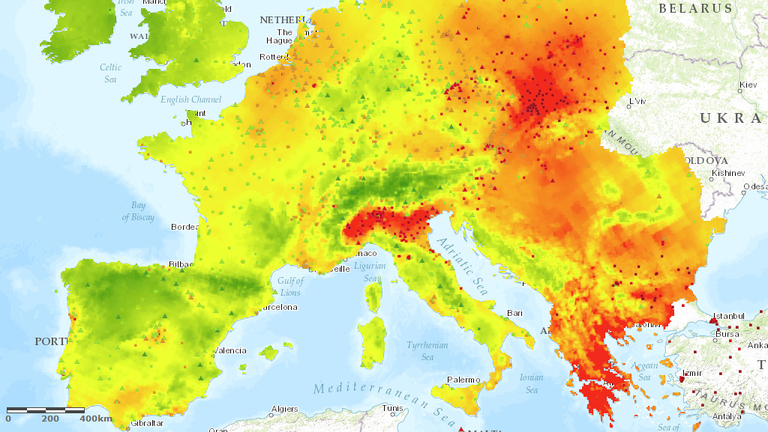

“Exotic doesn’t mean much. You’d consider Corsica exotic too. It’s a religion that originates from India. There are more than twenty thousand Sikhs working in the Agro Pontino, in appalling conditions, for as long as 12 hours a day and for ridiculous wages. Their employers and bosses themselves give them the drugs they need to withstand the pace in the fields and the greenhouses. Engels told me that back in the old days the capitalists used similar methods in some of the English factories.”

“This is the effect of illegal immigration.”

“And you are wrong, as usual. Almost all of them are regular immigrants. The Bossi-Fini law states that set quotas of migrants may legally enter Italy on condition that they already have an employment contract in place before leaving their country. This is usually a farce, since this is almost impossible; but farces can turn into tragedies. There are recruiters who tour villages in Punjab and sell full packages on credit: employment contract, journey, accommodation. Migrants get into debt to the tune of 4 to 8 thousand euros, and at this point they’re at the mercy of these middlemen, who can force them to accept any job at all in order to pay their debt back. These recruiters are linked to the mafias who rule the roost in the Fondi market and to the gangmasters, who withhold part of the workers’ wages. And employers, who instantly kick them out if they dare complain and keep thousands more euros in exchange for signing the contract, which is needed to get and renew the stay permits.”

“Yes, that’s horrible. But look: why do they accept it?”

“Precisely because quotas are regulated! That’s why the distinction between legal and illegal immigrants suits bosses: it sets a hierarchy. In order to stay afloat and obtain a permit you become vulnerable to blackmail. By the way, who told you they accept it? Look down there.”

They had landed in 2016. A balloon was floating above one of the squares in Latina. Diego was thrilled at recognising a square fascist-style building. He took the spyglass to assess the crowd in the square.

There must had been about four thousand people. As usual, there was a blaze of red flags. They were very orderly listening to speeches in some Asian (Diego thought “exotic”) language, delivered after climbing on one of those large billboards mounted on vans. Almost all of them were men with brown skin, some with very dark and prominent beards; several wore trade union caps, others had colourful turbans. Who knows whether they were also carrying their kirpan, the dagger all Sikhs are bound by their faith to carry?

“They are on strike. They will win a pay rise up to a more decent level.”

“How much?” Diego asked while still holding the spyglass.

“Five euros an hour,” the ghost replied.

7. No-border Lenin

Marx and Engels committed their entire lives to build parties, movements and international organisations of – guess what? – Marxist inspiration. Nevertheless, they never took public office; they didn’t even sit on a condo board. The first Marxist who took political power at the head of a revolution for longer than a few days was Lenin. From this standpoint, his opinion on immigration seems to be more relevant in understanding how to put internationalism into practice in terms of political programmes.

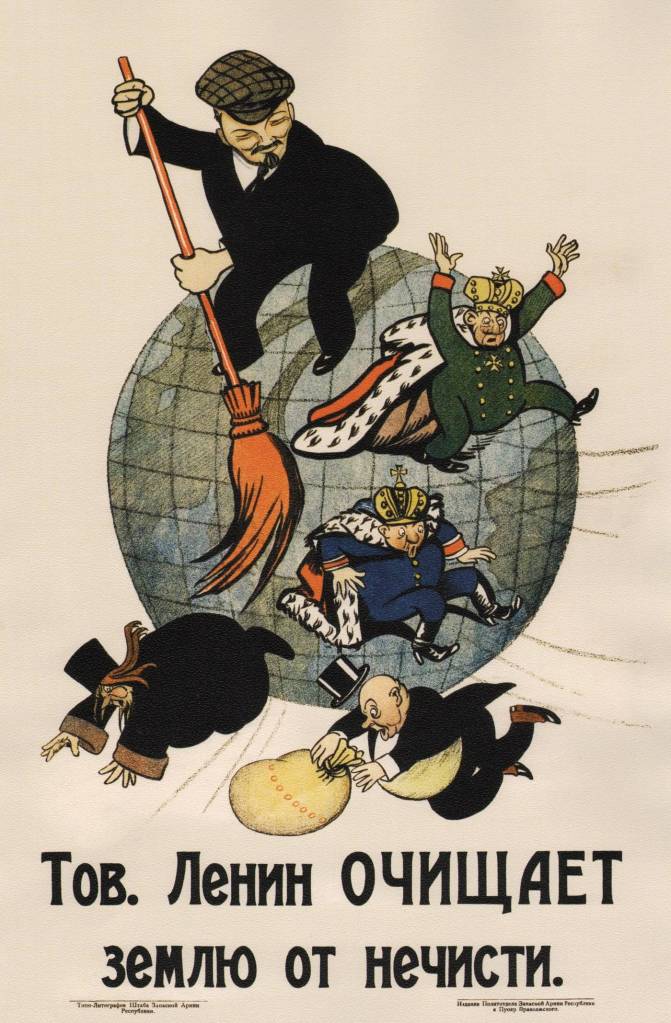

Our friend Diego hangs out with so-called “sovereignists” (“left-wing sovereignists”, obviously!) and since sovereignists not only love the Italian fatherland but, above all, the Russian fatherland, led by Presidentissimo Putin. Usually in that cultural milieu they want to score a bullseye by enrolling in the anti-immigrants’ ranks the quintessential trait d’union between Russia and Marxism: Lenin himself. That would be a nice shot, because they would get a uber-Russian, two-faced Janus, available for deployment in any argument. Are you right-wing? Take Putin, homophobic and anti-immigrant. Are you left-wing? Take Lenin, who is almost the same thing.

Here we must place a small obstacle in the way of this project. The obstacle is historical reality.

Lenin took part in the Second International (the First was dissolved in 1876–77) in which he represented the most left-wing faction. He clashed with the dominant line inside the organisation until he broke off all contact with the major parties that were part of it, and that put an end to the International just before the outbreak of the First World War. The fundamental reason for this break could be described, in modern terms, as follows: the majority of socialist parties adopted a “national sovereignty” line, supporting their national bourgeoisie against the others during the War.

Lenin struggled against all this. He was convinced that these political positions were the betrayal of Marxist Internationalism and he founded the Third International, namely the Communist International based in Moscow.

Long before this, back in August 1907, the Second International held a World Congress in Stuttgart. Lenin wrote a report from that Congress showing the beginnings of the future “sovereignty” degeneration of big socialist parties. For instance, Lenin criticised indignantly the attempt by some socialists from the most rapacious countries to approve a motion that could justify every form of colonialism (even though it was “socialist-colonialism”). This venture was abandoned but as a symptom it concerned Lenin a lot:

“This vote on the colonial question is of very great importance. First, it strikingly showed socialist opportunism, which succumbs to bourgeois blandishments. Secondly, it revealed a negative feature in the European labour movement, one that can do considerable harm to the proletarian cause, and for that reason should receive serious attention.”

Another debate during which confused positions emerged – and, in this case, were defeated with a very large majority – was the one about women’s issues and, in particular, about the right to vote: a minority position held that, based on tactical sophistries, it was first necessary to fight to obtain the male right to vote and only then to obtain that right universally. We flag this to remind ourselves that socialist and communist movements never set aside the struggle for civil rights, while its denigration is Diego’s hobbyhorse.

There is, however, an interesting passage in Lenin’s report about labourers’ migration. In fact, the Socialist Party of America (which had already tried, working with the Australians and Dutch, during the earlier Congress) had come up with this proposal: “To combat with all means at their command the wilful importation of cheap foreign labor calculated to destroy labor organizations, to lower the standard of living of the working class, and to retard the ultimate realisation of Socialism.”

The American delegate Hillquit defended the proposition to limit immigration blaming, in particular, Chinese people and others from less industrialised countries “who are incapable of assimilation with the workingmen of the country of their adoption”. This is the same hogwash we hear nowadays about Africans or Muslims, considered unable to “integrate” into our society. This horrible proposal was defeated. This is what Lenin wrote about it:

“A few words about the resolution on emigration and immigration. Here, too, in the Commission there was an attempt to defend narrow craft interests, to ban immigration of workers from backward countries (coolies—from China, etc). This is the same spirit of aristocratism that one finds among workers in some of the ‘civilised’ countries, who derive certain advantages from their privileged position and are, therefore, inclined to forget the need for international class solidarity. But no one at the Congress defended this craft and petty-bourgeois narrow-mindedness. The resolution fully meets the demands of revolutionary Social-Democracy.”

Oh dear! But this is exactly the opposite of what Diego is telling us, namely that the “globalist and snowflake lefties” are petty-bourgeois and detached from the proletariat, and for this reason defend immigrants! According to Lenin, it was precisely those who wanted to ban immigrants who were actually acquiescent to bourgeois ideology and their interests. Furthermore, as claimed by Lenin, the fact that the demand to stop immigration was spreading among some workers in Western countries was an indication that the bourgeoisie had “bought” a privileged layer of the working class.

The controversy with the American Socialists did not calm down over the following years. Notwithstanding Stuttgart and protests from the Japanese Socialists, the Socialist Party of America insisted on a “left-xenophobic” standing. In a letter to another group of American comrades, in 1915, Lenin wrote:

“In our struggle for true internationalism & against ‘jingo-socialism’ we always quote in our press the example of the opportunist leaders of the S.P. in America, who are in favor of restrictions of the immigration of Chinese and Japanese workers (especially after the Congress of Stuttgart, 1907, & against the decisions of Stuttgart). We think that one cannot be internationalist & be at the same time in favor of such restrictions. And we assert that Socialists in America, especially English Socialists, belonging to the ruling, and oppressing nation, who are not against any restrictions of immigration, against the possession of colonies (Hawaii) and for the entire freedom of colonies, that such Socialists are in reality jingoes.”

“Jingoism” refers to an extreme patriotism, in the form of aggressive or warlike foreign policy. The “jingo-socialists” today are those we’d call rossobruni (red-brown, “National Bolsheviks”).

Lenin deals with this topic several times in his writings. During 1913, he writes a brief article dealing mainly with immigration in America, but also treating migrations in general. Quite often xenophobes argue that the anti-capitalist left is not aware of the fact that in the present age capitalism itself creates and plans migrations. We are obviously aware of this; the main point is that this is not enough to decide which side to take. This is how Lenin tackles the issue:

“Capitalism has given rise to a special form of migration of nations. The rapidly developing industrial countries, introducing machinery on a large scale and ousting the backward countries from the world market, raise wages at home above the average rate and thus attract workers from the backward countries. […] There can be no doubt that dire poverty alone compels people to abandon their native land, and that the capitalists exploit the immigrant workers in the most shameless manner. But only reactionaries can shut their eyes to the progressive significance of this modern migration of nations. Emancipation from the yoke of capital is impossible without the further development of capitalism, and without the class struggle that is based on it. And it is into this struggle that capitalism is drawing the masses of the working people of the whole world, breaking down the musty, fusty habits of local life, breaking down national barriers and prejudices, uniting workers from all countries in huge factories and mines in America, Germany, and so forth.”

Undoubtedly this thought is more complex than racist memes and Salvini’s blogposts: it is a dialectic thought. At the same time, Lenin states that emigration is a dreadful matter, a disgusting business opportunity for capitalists, yet he is of the opinion that migration has a progressist and even revolutionary value. And how does he label those who refuse this truth? Reactionaries. Nowadays, we would call them fascists, or something along these lines.

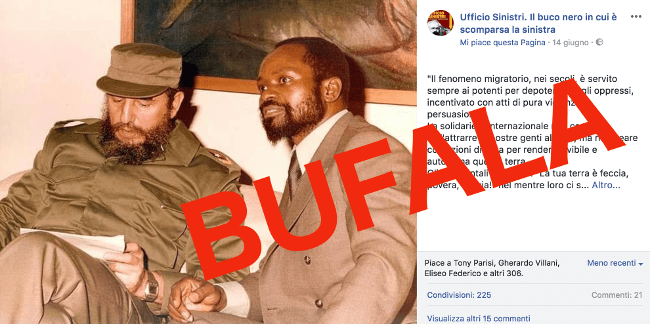

In the comments below the post, someone who knows Machel’s views and biography well (he was also a migrant) enquired about the sources used in the post; it soon turned out that the extract from the speech had been blatantly fabricated. After being chased a few times, Vallepiano came up with the title of a book, a rare collection of talks by Machel; however, Lorenzo Vianini from the Nicoletta Bourbaki group was able to trace it that same day and having assessed it, established that no such sentence existed; on the contrary, the content stated quite the opposite. These are typical methods adopted in rossobruni (literally “red-browns”, namely “Communist”-Fascist crossover) circles. We had already encountered a similar approach with the fake meme in Pasolini’s style “You see, dear Alberto…” created and circulated by the same circles. [Wu Ming]

En passant, let us also point out that according to Lenin, capitalism indeed triggers migration, but not due to an international plot hatched to deceive migrants, who would have remained at home, if only they “knew the truth”. Actually, the wage gap forces the proletarian masses to move from country to country for commonsense reasons.

And what about national borders? This topic suits customs officers, and seemingly thrills those like Diego. Are you perhaps trying to tell us that Lenin was a “no-border” hippie, a cosmopolitan for whom borders are insignificant imaginary lines? Not quite, but that’s where we’re heading:

“The bourgeoisie incites the workers of one nation against those of another in the endeavour to keep them disunited. Class-conscious workers, realising that the break-down of all the national barriers by capitalism is inevitable and progressive, are trying to help to enlighten and organise their fellow-workers from the backward countries.”

This last sentence might sound quite patronising towards workers from poor countries, however just a few lines earlier the author himself explains how at times those who provide valuable examples of class struggle to indigenous workers are indeed immigrants:

“Workers who had participated in various strikes in Russia introduced into America the bolder and more aggressive spirit of the mass strike.”

This observation reflects events occurring in the last few years in Italy very well. On the one hand, foreign workers’ participation has been increasingly integrated in the unions and in the struggles of Italian workers, while on the other hand they represented the peak of particularly audacious and fiery protests on several occasions (especially in agriculture and logistics).

Lenin deals again with this topic in 1916 when he writes one of his masterpieces, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. In this text, he states that if in the previous phase of capitalism the migration of the labour force (excluding the slave trade) occurred mainly from Europe, in the imperialistic phase the import of workforce was mainly from the colonies and the poorest countries. Imperialism exports capital and military troops to the colonies, and in turn imports raw materials and labourers from them:

“One of the special features of imperialism connected with the facts I am describing, is the decline in emigration from imperialist countries and the increase in immigration into these countries from the more backward countries where lower wages are paid. […] In France, the workers employed in the mining industry are, ‘in great part’, foreigners: Poles, Italians and Spaniards. In the United States, immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe are engaged in the most poorly paid jobs, while American workers provide the highest percentage of overseers or of the better-paid workers. Imperialism has the tendency to create privileged sections also among the workers, and to detach them from the broad masses of the proletariat.”

Lenin employs a critique which is the exact opposite of the one often purveyed, according to which immigration has created a layer of semi-slaves detached from the mass of workers. On the contrary, Lenin states that the most worrying phenomenon is the formation of a privileged layer of indigenous workers looking down on the others, including immigrants. Nowadays, this analysis ought to be deeply revised due to the decolonisation process, the great growth of the proletariat in Western countries, and the proletarianisation of the middle classes. Nevertheless, it is still representative of the Leninist approach: the problem is not represented by the immigrants and the lowest layers of this class, the problem lies in the detachment of the highest layers and in those attempting to provide them with a political voice.

The year following the publication of this text about imperialism is 1917, the year of the two revolutions. Lenin begins 1917 as a refugee and ends it as the political leader of Soviet Russia. This is the perfect occasion to observe how his ideas about immigration were applied to reality.

Obviously, a Russia after the October Revolution, shattered by World War I and by a civil war, engulfed by counterrevolutionary intrigues of every kind and huge economic problems, wasn’t really the target of vast streams of immigration. On the contrary, there was a huge number of emigrants: aristocrats and rich bourgeois escaping from the Revolution, political opponents and economic migrants from various social classes. However, except for political and military reasons, the attitude during the early years – that is, before Stalinism – was to realise the Bolshevik political programme to abolish passport controls, both for internal (one of the most hated characteristics of the tsarist regime, reintroduced by Stalin in 1932) as well as external travel.

The Constitution of the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic, written in 1918, more than being just a juridical authority, is a political document that declares the long-term objectives and the general principles of the new regime. On immigration, it expresses a position of radical opening of the borders:

“Art. 20. In consequence of the solidarity of the workers of all nations, the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic grants all political rights of Russian citizens to foreigners who live in the territory of the Russian Republic and are engaged in work and who belong to the working class or to the peasantry who do not use other people’s labour. The Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic also recognises the right of local soviets to grant citizenship to such foreigners without complicated formality.

Art. 21. The Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic offers shelter to all foreigners who seek refuge from political or religious persecution.

Art. 22. The Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic, recognizing the equal rights of all citizens, irrespective of their racial or national connections, proclaims that it is contrary to the fundamental laws of the Republic to establish or allow any privileges or advantages on this basis, as well as any kind of oppression of national minorities or limitation of their equality.”

So: according to article 20, free immigration and citizenship for everybody; according to article 21, hospitality for all refugees; according to article 22, absolute prohibition of racial and ethnic discrimination. A left-wing party so Leninist as to adopt such demands in its programme would certainly be accused by Diego as being in the service of globalised capitalism. How many revolutions did Diego take part in? None? Ah, there it is: we’d rather rely on October, I daresay.

8. The last night

He hoped to see a helicopter, a seaplane, a spaceship. But that fourth night, Karl Marx’s spectre did not show up again. Diego went upstairs, a bit disappointed, and slept all night.

The next morning, he was still a little shaken. He suddenly craved to read some books, to study. Perhaps it was the right time for a change.

The memories of the ghost, however, were already vanishing. Everything that happened seemed unreal and inexplicable to him. It could not have happened, neither the journey with Marx’s spirit nor all those struggles waged by aliens, uprooted turbo-slaves, puppets of bourgeois cosmopolitanism; and, what’s more, what were all those flags of the snowflake Left, concerned only about gay and civil rights, doing in the fields and on the factory floors? Implausible, dream-like, false.

Nevertheless, he decided to check every single event, one by one, on the Internet to see whether they were true or not, to check their background, to discover what happened afterwards; to search the newspapers to see if other similar stories were showing up, in other sectors of the economy, with other demands, and what links they had with Italians, and who was following them.

But something else happened: he received a text from an “Adriano CasaPound”. The text said: “You read about the nigga in Rozzano? Jot down a piece for the Primato, come on.”

He picked up his phone from the desk and saw that it was on top of a pile of overdue bills: power, gas, broadband… His contract as a lecturer with the Comunione & Liberazione University was ending next September.

He replied: “I’m writing it today.”

“Good, camerata, good. Nobis!” Adriano texted back.

Diego shook his head to chase the disturbing thoughts away.

A lemur, he was just a lemur.

9. In the good ol’ days… you would have grossed out the Left just the same

It would be impossible to explore the entire history of the Left worldwide, with all its different shades of coherence and anti-capitalism, to find out where and when an attitude on immigration similar to Diego’s has ever been hegemonic within a party or trade union or social movement.

Based on the analysis above, it seems that we could exclude that this was the case for Marx, Lenin and all their associates. However, when we discussed Lenin’s position, we saw that distorted anti-immigration political stances indeed did emerge, here and there, in the socialist-communist international movement, compelling others to fight a theoretical battle in defence of the fundamental ideas of Internationalism. The Third International, founded by Lenin and Trotsky and joined by Gramsci and Bordiga as representatives from Italy, struggled with these kind of topics as well. During its fourth congress, in 1922, the participants discussed the “oriental issue”, or what today would be called the “colonial issue” or the “Third-World issue”.

As had become clear some years before at the Second International meetings, the countries where the virus of xenophobia had most contaminated the Left were the richest countries with access to the oceans: the UK, Canada, USA, Australia, Japan. For social, cultural, historical and just geographical reasons – boats crossing the ocean are more conspicuous than land migration, like the boats and rescue ships in the Mediterranean today, and bring people from the remotest countries – Unions and the Left leaning towards reformist ideas in these countries proposed various forms of immigration regulations or even blockades, sometimes in a selective way against countries deemed as more “barbarian”.

This issue is dealt with extensively in the section The proletariat’s duties in the Pacific:

“In view of the coming danger, the Communist Parties of the imperialist countries – America, Japan, Britain, Australia and Canada – must not merely issue propaganda against the war, but must do everything possible to eliminate the factors that disorganise the workers’ movement in their countries and make it easier for capitalists to exploit national and racial antagonisms. These factors are the immigration question and the question of cheap coloured labour. Most of the coloured workers brought from China and India to work on the sugar plantations in the southern part of the Pacific are still recruited under the system of indentured labour. This has led to workers in imperialist countries to demand the introduction of laws against immigration and coloured labour, both in America and Australia. These restrictive laws deepen the antagonism between coloured and white workers, which divides and weakens the unity of the workers’ movement. The Communist Parties of America, Canada and Australia must conduct a vigorous campaign against restrictive immigration laws and must explain to the proletarian masses in these countries that such laws, by inflaming racial hatred, will rebound on them in the long run. The capitalists are against restrictive laws in the interests of free importation of cheap coloured labour and with it the lowering of the wages of white workers. The capitalists’ intention to take the offensive can be properly dealt with in only one way – the immigrant workers must join the ranks of existing trade unions of white workers. Simultaneously, the demand must be raised that the coloured workers’ pay should be brought up to the same level as the white workers’ pay. Such a move on the part of the Communist Parties will expose the intentions of the capitalists and at the same time graphically demonstrate to the coloured workers that the international proletariat has no racial prejudice.”

The system of indentured servitude is quite similar to the debts that Sikh immigrants working in the Agro Pontino incur with workforce mediators (reeking of mafia and gangmasters) not a century ago, but here and now. But who knows whether Diego has ever heard of them?

Since the late 1920s, a lot has been going on: Stalinism, the people’s fronts, “people’s democracies”, decolonisation, Maoism, more or less eclectic revolutionary movements, the transformation of many communist parties from Leninist revolutionary vanguards to mass parties more indulgent towards capitalism… The Left has been missing much of the theoretical rigour we have seen in the examples mentioned so far. Nevertheless, nobody has ever taken the kind of anti-immigrant stances of faux Marxist nationalists which Diego defends in our time.

Consider, for instance, Paolo Cinanni (1916-1988). A partisan during the Italian Liberation War and the leader of several farmers’ fights in its aftermath, Cinanni was an intellectual of the Italian Communist Party, with which he had a troubled relationship. Together with Carlo Levi, he founded the Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Emigrati e Famiglie (the Italian Federation of Emigrant Workers and Families, FILEF for short). In the framework of FILEF he gave birth to his most important theoretical work, Emigration and Imperialism. We mention Cinanni because a friend of Diego read about him in a comment on some anti-euro blog and brought him up in a low-grade debate on Twitter.

A very childish attitude underlies the instrumental exploitation of this author – and many others – in order to support the closure of borders: you take a piece of analysis and suggest it implies a practice similar to… Salvini’s.

This approach is particularly irritating and insulting in the case of militant authors, like Cinanni, who wrote unmistakably which political practices derive from their theoretical analyses. For instance, it would take a lot of guts for a nationalist to quote the following excerpt as though it were supporting their ideas:

“Emigration creates, as a matter of fact, decay, and this provokes new emigration, in a spiral process that leaves breathless our regions where this exodus occurs. The only commodity these regions continue to produce is the workforce, but with its departure they lose not only the expenditures incurred for its formation – more and more qualified and, hence, more and more expensive – but they lose the surplus value it produces in the regions and in the countries where it is employed, in particularly exploitative conditions.”

“Did you see that?!” Diego gets excited. “Cinanni says emigration is a bad thing that causes exploitation.”

Let’s give Diego a cup of chamomile and explain to him that, with all due respect, we didn’t need Cinanni to tell us: we all have relatives who are emigrants and they would usually have preferred to avoid it. But mostly we are all aware of the miserable conditions of Italian provinces where there has been and is large-scale emigration, internal or international, especially from the southern and the island regions.

What Cinanni says is that emigration impoverishes the country of origin in favour of the countries of destination; in today’s case, it transfers economic resources from the immigrants’ countries of provenance to benefit Italian capitalists. In other words, Cinanni claims that immigration is an economic advantage for the richer countries, which is precisely the opposite of what today’s xenophobes claim, that immigrants impoverish Italy. He even goes so far as to maintain that the countries of destination for migrants should compensate the countries of departure economically, something that is not accomplished by the remittances sent by migrants.

Cinanni’s analysis is also incompatible with the theory that immigrants create unemployment; indeed, Cinanni explains that, if anyone, the emigrants are responsible for it, demonstrating that in capitalism the number of employed (and unemployed) workers is not a fixed but a dynamic variable, just as Marx thought.

But if for the communist Cinanni, emigration is a capitalist evil (one of his texts is entitled The evil of emigration), isn’t he saying that halting immigration is a socialist virtue? No. He himself explains it very clearly:

“Migration for work purposes as it happens today incites competition within the working class itself; although anyone knows that immigration allows greater leeway to the production process and broadens the range of sectors of production, accelerating the overall development in the country of immigration, it is not rare for the foreign worker to hear that he steals jobs and bread from the local worker.

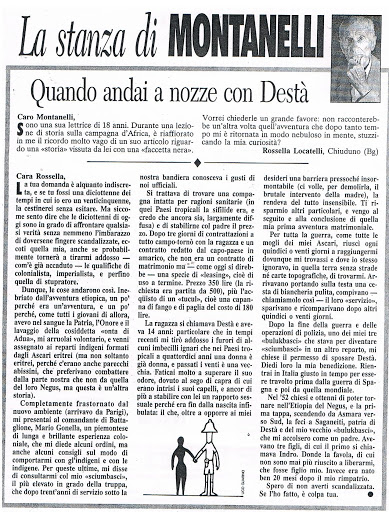

It is the ruling classes themselves that on the one hand promote immigration and on the other fear the unity of local workers with immigrants. They also fuel the same xenophobic campaigns, taking their cue from the most diverse events and occasional events. In this way, within Italy itself, the newspaper owned by FIAT 1 conducts in Turin a systematic campaign against southern people. In Switzerland it is the industrialist Schwarzenbach, leader of the anti-foreigner party, who runs the raving xenophobic campaign, influencing the most naive and inexperienced local workers to the point of crime, killing innocent victims among immigrant workers.”

To Cinanni, as to us, xenophobia is one of the bosses’ weapons that does not stand against capitalist migration politics, but rather complements it.

Once again, we face a dialectic thought, which requires some effort in order to understand the contradictions. If it is true that capitalists try to divide employees in order to better exploit them, it is also true that by itself immigration does not cause economic problems of a general nature, since it tends to produce, at first, economic growth proportional to population growth:

“Proportionally to the mass of immigrant workers, production increases accordingly in all sectors; the demand for consumer goods increases on the market, without this resulting – where there is no abusive speculation – in any disturbance to the economy of the country, for immigrants always produce more than they consume, representing the best guarantee against inflation.”

Therefore, the point is not to defend the national economy against a catastrophic invasion, since there is no such threat and the national economy will likely benefit from the supply of immigrant workforce, but rather to defend the living standards of blue collar, white collar and other wage-labourers, in other words, to seize larger shares of income from the hands of the bosses. How to do this? At the outset, Cinanni debunks the Italians first! slogan (or Germans first, or Belgians first, or, as in his example, EU citizens first):

“In our opinion, every immigrant workforce must “cost” the economy that is employing it the same as the local workforce. Indeed, every preference plays in the opposite direction, and every difference in treatment puts workers in competition with each other, breaking the unity of the labour market, and undermining, together with class unity, any prospect of social advancement.

Emigration shall not become the modern ‘reserve army’, with which the local working class is blackmailed; if the immigrant workforce costs less allowing Capital a higher profit, objectively – even without their awareness – they compete with local workers, causing the rage of discrimination, civil ostracism, and xenophobia.

This should be avoided, and it is especially important that the working class and its organisations become aware of it and require an effective ‘equivalence of labour cost’.”

According to Cinanni, immigrants are not a reserve army of labour, since they have similar employment rates as local people. Using slogans like Italians first risks rendering immigrants as a reserve army of labour: they all become unemployed and so economically separated from the local indigenous working class, easy prey for “wage dumping” (that is, paying wages much lower than is normal in an industry). Conversely, a vital necessity for the labour movement becomes that of equalising the cost of immigrant and indigenous labour, that is, raising the wages of immigrants to equality.

Some might reply that it is utopian, since immigrants are tramps living in shacks, they are Lumpenproletariat, they cannot catch up. Well, nowadays in Italy this is false. Income distribution proves it.

Wage levels by citizenship in Italy, 2011, 2nd trimester

| Italians | EU foreigners | Non-EU foreigners | EU foreign/Ital | non-EU foreign/Ital | ||

| average | 1299 | 1024 | 978 | 79% | 75% | |

| median (p50) | 1234 | 1000 | 1000 | 81% | 81% | |

| 1st decile (p10) | 670 | 450 | 500 | 67% | 75% | |

| 1st quartile (p25) | 1000 | 700 | 700 | 70% | 70% | |

| 3rd quartile (p75) | 1520 | 1200 | 1200 | 79% | 79% | |

| last decile (p90) | 1925 | 1500 | 1400 | 78% | 73% |

It is not straightforward to read these data, but what they say is that half of non-EU citizens are poorer than three-quarters of Italian citizens. The other half of non-EU citizens, therefore, earn more than the poorest quarter of Italian citizens. The same holds true for foreign EU citizens (among whom Romanians are the most represented minority). This is good news: it tells us that after all, even though the immigrants earn clearly less on average, there is no ethnic stratification as foreign proletarians belong to the same class as Italian proletarians, and they are roughly mixed from the remuneration point of view. Divide and rule? They try, but they have succeeded only to some extent. Equality is not out of reach, we just have to struggle: everybody can benefit from it (except for the capitalists).

And what does Cinanni say exactly about the likes of Diego, the “leftist” xenophobes who would correct the “do-gooder” politics of left-wing parties and unions introducing slogans against immigration? Well, he doesn’t mess around:

“Nowadays, in many countries, even big labour organisations seem to be affected by xenophobic leprosy; certain trade unions close themselves off in the most blind corporatism, without being able, however, to guarantee the fundamental demands of the local working class, in whose name they claim to side with anti-foreigner discrimination. Actually, even the union bosses’ good faith is doubtful: despite knowing that on an economic level immigration boosts the economic development of the country; despite also being aware that on a union level, the contribution of migrant workers could represent a decisive support to strengthen the bargaining power of the whole working class; and that on a political level, the unity of the whole working class might represent – for instance, in Switzerland – a stable bulwark against every social and anti-democratic convolution; despite knowing all of this, still some union bosses pretend to believe the fairy tale of the immigrant who ‘steals the bread’ of the native worker, and they too endorse – as it happened in Switzerland – the anti-foreigner referendum.”

Cinanni writes in an interesting “Middle-earth”, that is, Western Europe during the Seventies: an economic space where regions with strong emigration, like southern Italy, coexist with regions with strong immigration and, finally, more and more mixed regions. The latter is what Italy has become nowadays, both a land of emigrants (the “brain drain” or rather an “arm drain” of Italians to Germany, France, England and Canada) and the target of large migratory flows from Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Cinanni is right to raise the issue of how to hinder the destructive process of emigration, which is suffocating the South and which he sees as a continuation, in the post-colonial period, of the imperialist politics of domination and plunder of poorer countries and backward regions. He dismisses straightaway the reactionary idea of halting emigration and deporting migrants, which he calls useless and actually counter-productive. Instead, he invokes the overcoming of capitalism, socialism and the social and political struggle in the countries of origin, of course, but also in the countries of destination:

“Only in a balanced economy, planned according to social needs, do the productive forces develop together and at the same pace of the economic system, and in this case there will be no need for either emigration or immigration. However, under the domination of Capital, with the worsening of uneven development and territorial imbalances, the workforce drain worsens too and for this reason the single perspective and the single struggle for the return do not seem enough to us. In fact, it raises its demands and directs its action only towards the government of the country of origin, leaving emigration unarmed against the system that exploits it daily and the imperialist policy that causes the same underdevelopment in the countries of exodus. Therefore, the ‘going-back-home’ perspective, to which any emigrant is particularly sensitive, should be accompanied by the ‘compensation’ perspective, namely the effective equivalence of the cost between immigrant and local labour for the economy that employs both. This consideration originates from the most rigorous analysis of the phenomenon but, above all, represents the fundamental requirement to maintain the unit of the labour movement.”

In 2016 Rodolfo Ricci edited a collection of Cinanni’s writings, a mine of extremely valuable analyses which help understand how the issue was framed in the early Seventies. This publication is freely downloadable online (Italian).

After this inevitably cursory slideshow, one might well say that, in the second half of the 19th as well as in the first and the second half of the 20th century, all the sharpest communist thinkers supported similar politics in matter of immigration.

This politics is the exact opposite of what people like Diego preach.

This politics has always been anti-racist, border-free, internationalist, in favour of the unity of the working class.

If someone can’t swallow it, then the problem is theirs, but at least we hope that after this article, they will stop playing hide and seek.

10. Postscript

In this text we discussed migrants in general, not so-called refugees. The great majority of migrants living in Italy are regular immigrants (8% of the population).

A significant minority (one immigrant in every ten) are illegal migrants, i.e. without documents. Many of them will obtain these documents sooner or later, and they will become regular immigrants; and, conversely, regular migrants could lose their legal right to stay in Italy and become illegal.

Illegal migrants do not belong to a peculiar race: they are simply people treated as outcasts due to unjust (and inapplicable) bureaucratic rules. “Refugees” are an even smaller group — less than 1% of the population — that are talked about disproportionately on political grounds.

Diego often confuses these categories and thinks that in Italy millions of migrants are settled “in hotels” for 35 euro per day. Let’s try not to be as dumb as Diego.

Karl Marx was a migrant and a refugee of German, Dutch and Jewish origins. He emigrated in 1843 to France, from which he was deported in 1845 under pressure from Prussia, taking refuge in Belgium. He was arrested and deported from Belgium in 1848. Back in France and then in revolution-torn Germany, he was deported again in 1849 to France, but even France did not accept him. He then became a refugee in London.

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known as Lenin, was a migrant and a refugee of Russian-German-Swedish-Jewish descent. In 1900, he emigrated to Switzerland and then Germany. In 1902, he dodged the Bavarian police by relocating to London. Back in Russia after the 1905 Revolution, he fled the country as a refugee in 1907, returning to Switzerland, then France and briefly to London. During WWI he lived as an immigrant in a (now Polish) region of Austria-Hungary and in Switzerland, unable to get back to Russia until, as is well known, 1917.

Footnote

- La Stampa, one of the oldest Italian newspapers and symbol of the powerful industrial bourgeoisie in Turin and in Italy. FIAT is the largest automobile manufacturer in Italy and, at the time, in Europe.

Reading and viewing recommendations

■ Luca Lombardi, The miseries of the anti-immigrant Left (Le miserie della sinistra anti-immigrati, Italian)

■ David L. Wilson, Marx on Immigration. Workers, Wages, and Legal Status

■ Paolo Cinanni, Rodolfo Ricci (ed.), What emigration is. Writings of Paolo Cinanni (Che cos’è l’emigrazione. Scritti di Paolo Cinanni, Italian)

■ The Harvest, a movie directed by Andrea Paco Mariani. On farm gangmasters in the Agro Pontino and Indian labourers’ strikes.

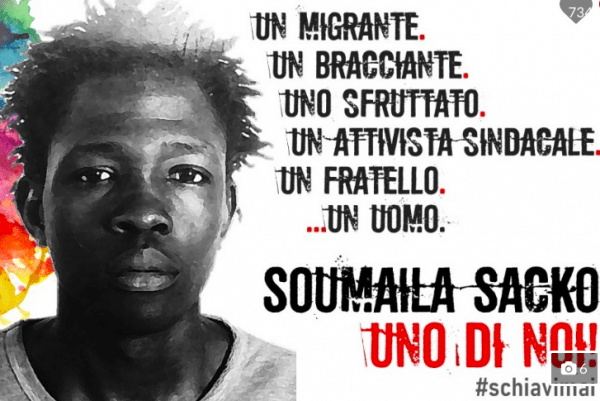

Dedication

Class struggle, whispered the spectre is dedicated to Soumaila Sacko, trade unionist of USB (Unione Sindacale di Base, Grassroots Trade Union) who was killed in San Calogero (Vibo Valentia, Italy) on June 2nd 2018.

Follow Mauro on Twitter → @maurovanetti

On the morning of May 27th, with the almost definitive results of the European election in Italy,

On the morning of May 27th, with the almost definitive results of the European election in Italy,

The national coordinator of the

The national coordinator of the  Newspapers report every day how our world is changing because of digital technologies. We often read about full automation, digitalization of life and the end of work. All these themes are interwoven in the sharing economy: apps that connect supply and demand to share a particular good. Foodora is not one of them, as nothing is shared. Foodora is part of the

Newspapers report every day how our world is changing because of digital technologies. We often read about full automation, digitalization of life and the end of work. All these themes are interwoven in the sharing economy: apps that connect supply and demand to share a particular good. Foodora is not one of them, as nothing is shared. Foodora is part of the  Le 4 Décembre prochain, le peuple italien sera appelé aux urnes pour le référendum sur la reforme constitutionnelle proposée par le gouvernement conservateur et pro-austérité de Matteo Renzi. Le sujet domine la vie politique italienne en raison de l’impact que pourrait avoir cette reforme sur la vie politique et institutionnelle italienne si elle est approuvée, mais aussi en raison de l’agitation qu’elle pourrait provoquer dans la politique italienne si elle venait a être rejetée.

Le 4 Décembre prochain, le peuple italien sera appelé aux urnes pour le référendum sur la reforme constitutionnelle proposée par le gouvernement conservateur et pro-austérité de Matteo Renzi. Le sujet domine la vie politique italienne en raison de l’impact que pourrait avoir cette reforme sur la vie politique et institutionnelle italienne si elle est approuvée, mais aussi en raison de l’agitation qu’elle pourrait provoquer dans la politique italienne si elle venait a être rejetée.