This post was originally published on Giap.

“We all have a friend, a lover, a relative, a neighbour, or a colleague who was unequivocally left-wing until a few years ago, but who has recently begun reading weird blogs, following perplexing Facebook pages, quoting certified bullshitters as if they were independent maîtres à penser, and echoing Matteo Salvini’s ideas—with a communist twist…”

A spectre flies us to the places of class struggle, where you can see that certain “Marxist” arguments against immigration not only aren’t Marxist at all, but are also a scam against workers. Against all workers, immigrant as well as local.

by Mauro Vanetti

editing: Camillo A. Formigatti, Roberto Amabile

translation: Antonio Scendrate, Ayan Meer, Camillo A. Formigatti, Claudio Mirabella, Daniele Contardo, Davide Tessitore, Filippo Ortona, Giovanni Vimercati, Marcello Bernardara, Mauro Vanetti, Niccolò Barca, Roberto Amabile, Simone Rossi, Stefania D’Urso, Tomaso Perani, Valerio De Sanctis

Contents of the first episode

1. First night

2. Those like Diego

3. Marx and the Reserve Army of Labour

4. Second night

5. Marx the do-gooder

1. First night

A spectre haunted the closing kebab shop. He was drunk and singing in French.

Three half-asleep students and a couple of Tunisians were watching him, intrigued; the Arabs recognised the bawdy song’s lyrics and laughed.

He ordered a kebab wrap to soak up his Barolo.

“Spicy?”

“With everything,” the man replied, shaggy-bearded and olive-skinned like a Saracen.

After devouring his nightly meal voraciously, he came back to his senses. He saw the name on the street sign and grinned: he had just had an idea for one of his tricks.

Diego sensed a cold finger hovering over his forehead and suddenly woke up, aghast at this unreal feeling. He opened his eyes and saw the translucent shape of an old man peering at him in the darkness, with lively eyes flashing under thick eyebrows.

“Boo,” said the phantom placidly, sitting beside the bed with his legs crossed.

Diego trembled and screamed, and fell onto the floor, scrambling towards a corner of the room.

“Gadzooks,” he babbled at last with a feeble voice. “Are you the Ghost of Christmas Past?”

“Oh please. I do look a bit like Santa but I’m definitely not. If I get to pick a holiday, I’m the ghost of May Day. Actually, I’m the spectre of Karl Marx.”

“Maestro!” Diego exclaimed, while falling on his knees at the ectoplasm’s feet.

“Maestro my arse. You don’t know a thing. I’m back because I need to show you something. Get back to bed, we’re going to fly.”

Diego complied without a word, still amazed by the supernatural turn of events. The spirit walked on the sheets in a very dignified way and took command, sarcastically eyeing the pastel-coloured pyjamas of his passenger. As Marx snapped his fingers, the room and the whole house disappeared, leaving only the bed floating among the stars. It started an impossible flight through space and time, at the end of which the sun had already dawned for a long time, one hundred yards below them, over the Apulian countryside.

“It’s 2011, it’s August and we are in Nardò, in the province of Lecce,” said Marx. “Look at what’s happening at that farm.”

Dozens of Africans had gathered at the entrance to a short and squarish building covered in pink and grey plaster, sun-burnt and weathered, with a flat roof like a Mexican pueblo. Makeshift tents were all over the place and a banner was hanging from the façade. Some Africans were loitering and lolling around the area, others were debating excitedly. As the flying bed approached and finally landed amidst the branches of a tall maritime pine, Diego noticed that almost all of them were smiling with a look of self-satisfaction.

“Scrounging refugees?” Diego asked, rubbing his eyes.

“No,” said Marx, grabbing the young man by the ear and dragging him. “Look more closely: striking farm labourers.”

An Italian man with a megaphone announced that the protest had reached its third consecutive day of strike in the tomato fields and expressed solidarity with the protest’s leader, a student from Cameroon who had been the object of mafia-style threats. A Ghanaian took the floor straight after him, explaining the demands: extra wages whenever the tomatoes have to be divided by size, a stop to undeclared labour, improved health and security standards, direct negotiation between bosses and workers, together with labour unions and an employment office of some sort but without any mediation role for the gangmasters. Then another one spoke, explaining in broken Italian that something also had to be done about a serious problem the immigrant workers were facing: the gangmasters withheld their documents in order to blackmail them, leaving them just with copies. He said that without documents and with that skin colour they were constantly at risk, as the police could easily give them hell; this was definitely another thing worth fighting for.

“Class struggle,” whispered the spectre, spellbound.

2. Those like Diego

We all have a friend, a lover, a relative, a neighbour, or a colleague who was unequivocally left-wing until a few years ago, but who has recently begun reading weird blogs, following perplexing Facebook pages, quoting certified bullshitters as if they were independent maîtres à penser, and echoing Matteo Salvini’s ideas—with a communist twist. Sometimes we are that person. And the subject on which so many of us have slipped is always the same: immigration.

Let’s analyse a typical conversation that could take place with this acquaintance of ours, whom we’ll call “Diego” now – for simplicity’s sake.

In general, the first thing Diego would do is shun racism, and profess his hatred for fascists and the Lega. To prove to us that he’s a bona fide comrade, he may even sing Bandiera Rossa without missing a beat, and list every time he voted like us, or went to a squatted social centre with us, or even marched in protest at our side. Mind you, he has not become a fascist.

However, he’s realised that “it’s our fault” if the right is rising. He says it exactly like this, emphatically stressing “our”—because he’s been mired in it until recently. Indeed, he goes on, the Left and comrades have ended up countering xenophobia with “do-gooder” and “no border” ideas that mirror those of Big Business. According to Diego, bosses need cheap foreign labour and hence they heartily support immigration.

Generally, a bit of bickering would ensue. But Diego tries to end it with what he thinks is the ace up his sleeve: “Even Karl Marx,” exclaims Diego, “explained that immigrants are the reserve army of labour!”

According to Diego, the reserve army of labour is made up of desperate workers uprooted from their homeland, used by employers to keep wages low. If the conversation is happening online, Diego will send us a link to one of these weird blogs he’s often browsing nowadays, where some of Marx’s quotes are thrown about to prove that going after migrants is helpful in order to defend the proletariat. If we’re talking in person, he’ll send us the link anyway, to make sure we read it later. Those like Diego love proselytising about what opened their eyes and led them beyond the “immigrationist” clichés bandied around by the globalist and radical-chic Left.

The name of this Facebook page is “Leftist and anti-racist, but against the foreign invasion.” I am not racist, BUT…

This article aims at debunking two false beliefs: that “real Marxists of yesteryear” justifies hostility toward migrants, and that anti-immigration policies benefit the class struggle.

Some may say these are merely marginal opinions, associated with a fringe of irrelevant provocateurs—no-one important manipulates Marx to support Salvini!

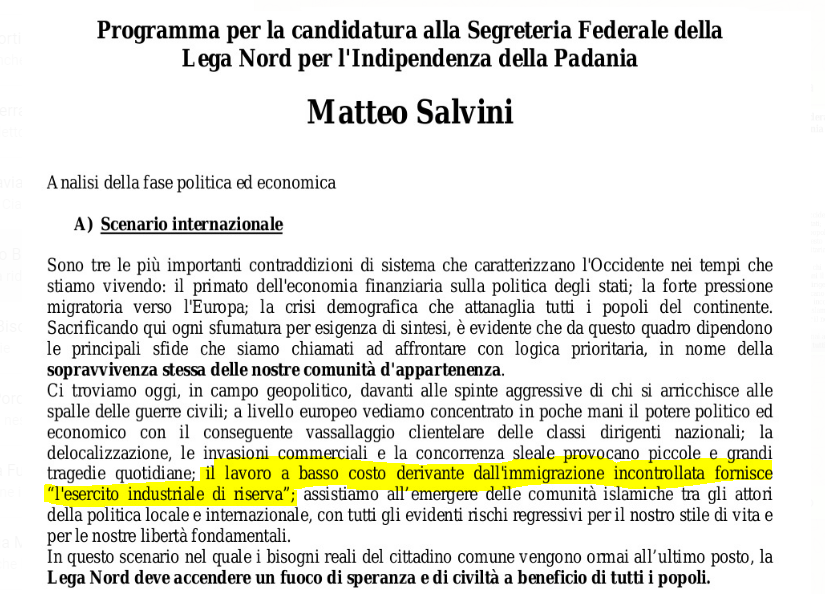

Alas, this is not true. Here’s the introduction to Salvini’s electoral manifesto for the Lega leadership:

Candidate Matteo Salvini’s Programme for the Federal Secretariat of the “Northern League for the Independence of Padania” (Spring 2017 and yes, that is the party’s official name! We mean, half the party’s name, the other one for voters in the South is called the “League for Premier Salvini”). In 2018, Salvini was appointed Minister of the Interior.

The highlighted sentence, “Low-cost labour derived from uncontrolled migration provides ‘the reserve army of labour’” is a fake quotation from Marx’s Capital.

3. Marx and the Reserve Army of Labour

Let’s start from this wretched reserve army of labour. Karl Marx talks about it extensively in chapter 25, section VII, book I of Das Kapital. The reserve army of labour is made up of unemployed people.

In Marx’s time, there were many simplistic beliefs according to which unemployment was due to the workers having too many children. The most notorious and brutal manifestation of this idea is Malthus’s theory of overpopulation, which described poverty as a natural consequence of the excessive fertility of the working classes. Since Italian workers nowadays have few children, today’s Malthusians, like our Diego, came out with a new — even duller — explanation: poverty in Europe is a consequence of the excessive fertility of Africans.

Marx, on the other hand, came up with a more sophisticated idea: it is capital accumulation itself, in the context of a market economy, that automatically creates a relative overpopulation, that is, a certain amount of workforce available for production but kept at rest. This relative overpopulation (that is, the unemployed and first-time job seekers) eventually becomes nothing less than a “reserve” within the proletarian “army” used by the companies. Just like the reserve of an actual army, this reserve army of labour can be mobilised whenever the need arises – which occurs regularly, as capitalism has a cyclical trend (expansion – crisis – recovery) and continuously revolutionises its production techniques by design, moving the workforce between different production sectors or towards newly-introduced sectors. If capitalism waited for new workers to be born and to reach working age every time it needed new recruits, it would crumble into ruin: so it has to enrol them as soon as possible, just as it must be able to get rid of most excess workers should the need arise.

Marx’s idea that a natural rate of unemployment exists in capitalism with no relation to demographics has meanwhile become mainstream, and even bourgeois economists now refer to natural unemployment and cyclical unemployment.

According to Marx, the reserve army of labour has three components: floating, stagnant and latent:

■ Floating [labour] overpopulation consists of dismissed: expelled from production, they try to re-enter it another way or sometimes, Marx says, they will emigrate. In Marx’s time youth unemployment was not a serious issue, so he mainly thought of adult workers as being replaced by young or even child workers; nowadays, we would include in this subcategory many unemployed young people who are looking for their first job.

■ Stagnant overpopulation consists of temps: well yes, contrary to what you might think, temporary employment also existed in Marx and Engels’ time. From the under- and partially employed, capital draws new full-time workers whenever it needs to increase its standing workforce.

■ Latent overpopulation is made up of rural population in a process of migrating to urban areas. Many migrants from semi-industrialised countries are part of this subcategory. (The largest share of foreigners in Italy, though, probably come from cities.)

As you can see, apart from latent overpopulation (now practically extinct in the West) the two other categories do not require the reliance of capital on external sources to fill the army of the unemployed.

An even more striking example comes from the Mezzogiorno, Southern Italy: countless people migrate from Southern Italy, yet this does not create a shortage of workers there. On the contrary, unemployment is peaking in exactly those areas with maximum emigration. Even Diego can understand that if we believe immigration creates unemployment, we should equally believe that emigration creates employment – but this is not what happens.

What effect does unemployment have on wages according to Marx (and almost everyone else)? It lowers them, of course. Obviously, competition among proletarians lowers the price of labour-power. This is one of the many advantages of the reserve army of labour for capitalists, while it’s the main rip-off for employed wage-earners. Without other factors to counterbalance that downward pressure (factors that fortunately exist!), the presence of natural unemployment would push wages down to subsistence levels.

A 2018 neo-fascist flyer reads: “What did Karl Marx say? Industrial reserve army? Immigration is needed to lower salaries, rights and welfare. To turn Europe into a Third-world country, to turn us all into a mass of wretched people, temp-workers exploited and without rights. The LEFT today doesn’t break the chains, it fights for them! Not AGAINST but FOR the DOMINANT FINANCIAL ELITES! As they blab about rights, about opportunities and emancipation they are actually domesticating us to new damnation and servitude!”

It’s a perfect example: falsified Marx, the concept of “industrial reserve army” reduced to empty words and bent to a racist point of view in order to divide workers..

As you can see, Marx didn’t think that capitalism needed a little help from Africa to exploit workers: its intrinsic dynamics were more than enough. But Marx wasn’t a fatalist either. He believed one could fight capital’s tendency to turn the proletariat into wretched people who can barely survive. He believed in this so much that he spent his whole life trying.

How did Marx suggest dealing with the reserve army of labour?

Surely not by declaring war against them. Guess what? He proposed integrating them into working-class struggles and possibly trying to have them reabsorbed into the working class itself: for instance, by decreasing working time to share available jobs among everyone, thus reducing unemployment and giving capitalists less chance to take advantage of it; or by making the working conditions of the stagnant overpopulation the same as everybody else, thus preventing firms from using casualised work.

Although they both spoke of the brutal and alienating character of that process, you won’t find appeals by Marx and Engels to stop the peasants from migrating to cities. On the contrary, we do read positive remarks by them about the progressive effect of such migration. This is how they describe the endeavours of the bourgeoisie to this end:

“It has created enormous cities, has greatly increased the urban population as compared with the rural, and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life.” (Manifesto of the Communist Party, chapter 1)

4. Second night

Diego wasn’t sleeping. Was last night just a nightmare? Was it really a spirit? What would Hegel say? Perhaps he would have tried to study the phenomenology of Spirit! Ha ha ha! No, it isn’t funny. His sense of humour had been affected too.

What if Marx’s spirit was right? Diego didn’t actually meticulously read all the books he had often cited. Some of them he had never read. Really, in 21st-century Italy, who reads Marx? Quoting him was a kind of homage. He just wanted to warn against immigrationist turbo-globalism…

The door opened.

“Let’s go, we’re leaving, hurry up!” the bearded spirit yelled, bursting into the room.

“By Jove! Where are we going?” the young man asked, running to grab a pair of shoes and a coat. He didn’t want to spend another cold night just in his pyjamas.

“We’re going to Emilia. I have a couple of stories to tell you.”

Diego made some space on the bed for the revived German philosopher, economist and revolutionary Karl Marx, who clicked his tongue. “We’re not taking that wreck. I’ve got my jet. Get in.”

“An aviogetto!” Diego uttered, worried and astonished, while a mysterious red jet with no pilot landed smoothly on the street. A stray cat was scared.

“I warn you,” Marx said after travelling for a few minutes, “we’ve almost arrived and you won’t like what you see. Shut up and learn something.”

The fighter landed in a field. It was night. Clamour and engine noises came from a warehouse on one side. On the other side, a long viaduct stood above the horizon. The two human figures quickly walked into the dark; the older one showed the way and when they came to the gates of the factory, he gestured to Diego to keep quiet and look.

There were different gates for the lorries and about ten badly-dressed guys were keeping an eye on them. They sounded Arabic. They appeared quiet, but alert. Some of them waved red flags in front of several white lorries that had stopped in the middle of the road. On the side of the white monsters, three letters were written: “GLS”. A young man switched his megaphone to siren mode and let it scream into the night. There were a few police cars.

One lorry was parked near the corner of the warehouse gate. Suddenly, it accelerated and turned right to break through the blockade. At that point, there wasn’t really a blockade as the protesters had already dispersed, but a balding man about 50 was still on the road, he was wearing a union hat and looked like a good guy.

The man saw the lorry, he was alarmed and ran in front of it, showing his hand, palms up. The driver didn’t yield and sped up. Maybe he was sure that the porter would step aside, maybe he was just bothered by the blockade and the idea that he, as an Italian, had to accept the demands of these North Africans, maybe he was forced to by his bosses. In any case, the lorry hit the porter, slammed him violently to the ground and eventually came to a halt.

The comrades of the man suddenly came running, shouting out their despair and their rage. Some surrounded the body on the ground, others tried to catch the killer and lynch him. Police stepped in to stop them; a man wearing a white shirt, one of the managers, came out of the warehouse.

Diego had turned pale.

“Let’s leave,” said the ghost, bleak. “That Egyptian man was a union leader; he will die. His name was Abd El Salam Ahmed El Danf,” the ghost explained while the red jet was taking off again, invisible to the porters mourning their comrade.

Marx was driving. Diego watched the Emilian countryside, the A1 motorway, the factories, the weird in-the-middle-of-nowhere high-speed train station, rapidly flowing under them; then again and again, one after another, awful square warehouses. The old man’s phantom pushed the joystick forward and the plane flew down, just a few metres over the ground, slowing down.

“Are we landing?”

“No, that’s enough for tonight, I just want to show you a tent. There it is!”

The tent, decorated with red flags, was standing a few steps away from the gate of yet another warehouse. A really modern-looking warehouse: white metal battens on every side, mirror glass. You could mistake it for a chemical laboratory, yet they just process pork meat. It seemed that another structure emerged from the front of the building, a kind of small triangle-based tower. On the top of the small tower, the sign: “CASTELFRIGO”.

In front of the tent, gathered around a fire in an oil drum, some tired but cheerful foreigners’ faces: one from Eastern Europe, one from Africa, two from China.

The fighter jet sped away above them and continued its flight.

“Many months of indefinite strikes, including hunger strikes, o renew the contract of workers employed by fake cooperatives and to put an end to illegal practices adopted by porterage cooperatives that broker workforce in the meat processing industry. Strike-breaking measures set up by CISL, police crackdowns, any amount of conniving by union bureaucrats. I ask you right now: do they look like “uprooted slaves” willing to be exploited to you?”

Diego hesitated. “They are indeed uprooted…”

“They’re growing their own roots…” answered the ghost; then he slapped him on the head. “…you moron!”

5. Marx the do-gooder

Karl Marx, like Friedrich Engels, lived in England for many years. At that time in England, there was both racism against Asian and African people from British colonies, as well as general xenophobia against people from other countries. Most immigrants came from Ireland, which was at the time still part of the United Kingdom.

Marx and Engels wrote a lot on the subject, shedding light on the miserable living conditions of Irish workers and how such conditions brought ethnic and social conflicts. They also wrote about the spectacular differences that existed between them, most of them being former farmhands or peasants from very poor areas, and the English working class, which had already settled into industrial capitalism. Nor did they hold back from criticising Irish nationalist political leaders.

Diego tells us that the founders of scientific socialism were certainly not “do-gooders”. We would be forced to say he’s right if we found in Marx’s texts something like that:

“And most important of all! Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians.

The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker, the English worker regards himself as a member of the oppressed nation, suffering an invasion: foreign invaders become a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination. The English worker justly defends his own religious, social, and national traditions against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the American Indians who tried to defend themselves against the Whites’ invasion to avoid ending up in reservations: how could one blame him?

This antagonism is artificially deadened and kept at bay by the globalist press, the ‘tolerant’ sermons of priests, left-wing satire doling out goodwill and piety towards the ‘poor Irish’. In short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes and their foolish servants. The ‘do-goodery’ is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.”

Where did Marx write these lines? Fucking nowhere. The first paragraph is his, but I invented everything else. This is not Marx: it’s Diego’s imaginary Marx. Let’s read instead the real Marx, in his letter to Sigfrid Mayer and August Vogt on April 9th, 1870:

“The King of a-shantee”. 1882 anti-Irish cartoon. The title is a pun between “king of shanty” and “king of Ashantee”, an African tribe. The mocking of poverty overlaps, through the depiction of Irish as negroids and monkeyish, a clear racist message. Source here. Other examples here.

“And most important of all! Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life.

In relation to the Irish worker, he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the Negroes in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.”

What have we just read? Exactly what it seems. Marx saw reality and knew exactly that there was bad blood between English and Irish workers. When in the Manifesto he writes “the working men have no country”, he describes the condition which objectively would make sense for them and to which they are pushed by the development of the world economy. Yet he knows, of course, that they are fraught with ethnic prejudices, religious prejudices etc. To Marx, however, this typically working-class sentiment of rivalry with proletarians of other nationalities is convenient for bosses and the bosses themselves stir it up continuously.

Marx never argues that capitalists promote do-goodery and tolerance towards immigrants; instead, Marx argues that the dominant class diffuses, more or less subtly, xenophobia and racism.

It’s interesting to note that even racist humour magazines are dangerous tools in the hands of the dominant class. Today we would say: anti-immigrant cartoonists like Marione or Krancic, right-wing singers like Povia (who, by the way, actually claims in a hideous song the nonsense that “Carletto Marx” agreed with him).

Basically, Marx says that workers who reason like Diego are like scabs: they get hoodwinked by the bourgeoisie and divide their own class. And he adds that this is the same even for immigrants who hate locals, although naturally he devotes less time to this.

But this letter tells us much more. Generally, migrations of the labour force are not a bourgeois plot: they happen spontaneously and at the initiative of the migrants themselves, to decide their own destiny and look for a better life. Capitalism automatically creates the conditions of economic disparity which feed migration; the bourgeois take advantage of that _a posteriori _for their own economic and political interests, as they do with anything.

In this particular case, however, Marx is pretty convinced there’s really a sort of capitalist conspiracy: Ireland, after all, is an inner colony of Britain, the latter determining the former’s agrarian policy, encouraging the depopulation of the island’s countryside. In fact, he talks about “forcible emigration”. Even so, Marx does not propose that the communists demand a policy of halting immigration. On the contrary, he recognises in this melting pot an opportunity for the First International he founded.

Workers’ organisation disrupts the plans of Big Business. Trends that, left to themselves (or rather, left to the bosses), would be reactionary, can thus be turned into something progressive. Labour-power is a special commodity and one of its characteristics is that it is not inert. Workers are human beings with a developable consciousness. All of Marxism is permeated with the awareness that class struggle (that is, the impossibility of regarding workers just as factors in production) shapes the world.

As closing remarks in the letter, having explained the importance of gaining the sympathy of Irish workers by defending the liberation of Ireland from the imperialist yoke, Marx describes with admiration the efforts of his daughter Jenny to inform the general public about the Irish question. He concludes by saying that it is crucial for the International to strengthen cooperation between Irish workers and workers of other nationalities, not only in Britain but also in America, where national divisions have always fragmented the labour movement in a particularly harmful way.

OK, it seems obvious, yet apparently it isn’t, so it’s better to write it down explicitly: according to the founders of the First International, workers of different nationalities should unite, both by forming links between the working class of one country and another, and, within each country, between native and immigrant people. That’s why it was called International Workingmen’s Association. Class brotherhood had to be promoted. Today, the xenophobes would certainly call them do-gooders.

The “do-gooders” of the First International.

This is what Marx proposed in 1871, the year of the Paris Commune:

“It is necessary that our aims should be thus comprehensive to include every form of working-class activity. To have made them of a special character would have been to adapt them to the needs of one section — one nation of workmen alone. But how could all men be asked to unite to further the objects of a few?”

This quotation answers yet another widespread rubbish argument, namely that it was Marx’s opinion that each nation should struggle separately. It is a misunderstanding born from a passage in the Manifesto which actually claims the opposite (“Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle.”)… but let’s keep that for another time.

In the interview, Marx continues:

“To give an example, one of the commonest forms of the movement for emancipation is that of strikes. Formerly, when a strike took place in one country it was defeated by the importation of workmen from another. The International has nearly stopped all that. It receives information of the intended strike, it spreads that information among its members, who at once see that for them the seat of the struggle must be forbidden ground. The masters are thus left alone to reckon with their men. […] By these means a strike of the cigar makers of Barcelona was brought to a victorious issue the other day.”

As with many of these writings, if Diego read it without understanding much he would get easily excited: in fact, here Marx is saying that the International stopped the import of foreign scabs. Yet it is how that matters: the International stopped the foreign strike-breakers organising the foreign workers by involving them in the common struggle. To the internationalists, it would have been unthinkable to ask the state (that is, the police) to stop the scabs by putting up walls at the frontiers. Rather, for as long as there have been cops in this world, they have always escorted blacklegs across the picket line.

Regardless, the deepest message is another one: one should always consider foreign workers – whom the ruling class would intend to use as cheap commodities to lower the cost of other commodities – as human beings who must be included, convinced, involved. In Diego’s rhetoric, instead, immigrants are objects or, at best, “slaves” to be pitied. It’s the same rhetoric as their exploiters’.

End of the first episode

Thanks to the great Winsor McCay for the inspiration.

contents of the second episode

6. Third night

7. No-Border Lenin

8. The last night

9. In the good ol’ days… you would have grossed out the Left just the same

10. Postscript

Follow Mauro on Twitter → @maurovanetti